This note walks through a hardware implementation of a simple processor and complete compiler for a programming language targeted at it. The processor architecture is designed to as simple as possible but provide a sensible target for the compilation of complex programs using simple strategies. The implementation of the processor and its supporting tooling is small and self contained so to be understandable and easily extendable. Besides being an interesting side project, my motivation was to create a complete example as a point of reference to explain how programming languages work and correspond to the underlying hardware of a computer processor, or to provide a useful reference for compilers and simulators, a starting point for another project or just a curiosity in itself.

First, to provide some background. The project is based on the Hex processor architecture that was designed by David May as a vehicle for teaching about how computers work at the University of Bristol, whilst being flexible enough to execute substantial programs and easily extensible. David provided a simulator written in C and a bootstrapping compiler written in an accompanying simple imperative programming language called X. The design of Hex draws on the Transputer architecture and the earlier Simple 42, particularly with the use of short instruction encodings, a prefixing mechanism for creating larger immediates and A, B and C registers for expression evaluation. These kind of architectural features made the silicon implementation of the Simple 42 and Transputers small enough to fit on a single chip in the technology of the day. X draws on the basic sequential features of the occam programming language but it not dissimilar to a small subset of C, for example. I include some more historical details at the end.

In my implementation, I have created a simple C++ toolchain with a simulator, Hex assembler and X language compiler, and a Verilog implementation of Hex. Before describing them, the next two sections introduce Hex and X.

Table of contents

- The Hex architecture

- The X language

- Hex processor integrated circuit

- Hex tooling

- A historical note

- Summary

- Similar projects

- Further reading

The Hex architecture

The Hex architecture is described in detail in a separate

PDF, but I will give a brief summary here

and focus on several important aspects for reference. Hex has four registers:

program counter pc, operand register oreg and the A and B registers

areg and breg used for expression evaluation. The architecture is

agnostic of a particular word size, but it has to be a minimum of a byte and

multiples of a byte. In the included implementation the word size is 4 bytes.

Hex has sixteen instructions (hence its name!) that are summarised in the

following table. Each instruction has a 4-bit opcode and a 4-bit immediate. The

immediate value can be extended using the prefix instructions to form a wider

value in the oreg, adding four bits per instruction. Operations beyond the

16 available encodings are made accessible by the OPR instruction that

encodes the operation type with its immediate. The instructions are grouped

into memory access with absolute or relative addressing modes, loading of

constants, branching, inter-register operations and supervisor calls.

| Opcode | Behaviour | Description |

|---|---|---|

LDAM |

areg := mem[oreg] |

Load from memory with an absolute address into areg |

LDBM |

breg := mem[oreg] |

Load from memory with an absolute address into breg |

STAM |

mem[oreg] := areg |

Store to absolute address from areg |

LDAC |

areg := oreg |

Load constant into areg |

LDBC |

breg := oreg |

Load constant into breg |

LDAP |

areg := pc + oreg |

Load program counter-relative address into areg |

LDAI |

areg := mem[areg + oreg] |

Load from memory with base and offset into areg |

LDBI |

breg := mem[breg + oreg] |

Load from memory with base and offset into breg |

STAI |

mem[breg + oreg] := areg |

Store to memory with base and offset from areg |

BR |

pc := pc + oreg |

Branch relative |

BRZ |

if areg = 0: pc := pc + oreg |

Conditional branch relative on areg being zero |

BRN |

if areg < 0: pc := pc + oreg |

Conditional branch relative on areg being negative |

BRB |

pc := breg |

Absolute branch |

PFIX |

oreg := oreg << 4 |

Positive prefix |

NFIX |

oreg = 0xFFFFFF00 | oreg << 4 |

Negative prefix |

OPR |

- | Inter-register operation |

ADD |

areg := areg + breg |

Add areg and breg and set areg to the result |

SUB |

areg := areg - breg |

Subtract areg and breg and set areg to the result |

SVC |

- | Supervisor call |

Prefixing

Prefixing using the PFIX and NFIX operations generates operand values in oreg larger than the 4-bit instruction immediate. For example, the

following instructions generate the value 16 in oreg and use LDAC to

assign it to areg :

PFIX 1 # oreg = oreg (1) << 4 (0x000010)

LDAC 0 # areg = oreg 16

Prefixes can be chained to extend the operand range, for example, generating the value 496 requires two positive prefixes before a load constant instruction:

PFIX 1 # oreg = oreg (1) << 4 (0x000010)

PFIX 15 # oreg = oreg (31) << 4 (0x0001f0)

LDAC 0 # areg = oreg 496

Negative values always require a negative prefix to fill the top most oreg

bits with ones, so to load the value -1 into oreg then areg:

NFIX 15 # oreg = 0xFFFFFF00 | oreg (15) << 4 (0xfffffff0)

LDAC 15 # areg = oreg 4294967295

And to load -512, a positive prefix is required to scale the negative value:

NFIX 14 # oreg = 0xFFFFFF00 | oreg (14) << 4 (0xffffffe0)

PFIX 0 # oreg = oreg (4294967264) << 4 (0xfffffe00)

LDAC 0 # areg = oreg 4294966784

Inter-register operations

The inter-register operations use the OPR opcode and consist only of

addition and subtraction. The group can be extended by implementing additional

immediate opcodes to add new operations to the processor (such as other

arithmetic and bitwise operations). The 4-bit immediate supports up to 16

inter-register operations without the need for prefixing, but many more with

prefixing and the according overhead to form larger immediates. The following

instruction sequence adds two numbers from fixed locations in memory, with the

result written to areg:

LDAM 1 # areg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (7)

LDBM 2 # breg = mem[oreg (0x000002)] (9)

OPR 1 # ADD areg = areg (7) + breg (9) (16)

A special inter-register operation is a supervisor call that transfers

control to the system to complete an action such as read or write from a

file, or to halt the program. The supervisor call type is encoded in the

oreg and arguments and return values specific to the call type are passed

and returned on the stack using the standard calling convention. An example

code sequence to invoke the exit supervisor call is:

LDAC 0 # Set areg to 0, the exit opcode value.

LDBM 1 # Load the stack pointer in breg.

STAI 2 # Store areg into stack offset two as a parameter.

LDAC 0 # Load the exit opcode.

OPR SVC # Perform the supervisor call

With the following execution trace, noting that the simulator implements the system call directly rather than being handled by a kernel routine:

LDAC 0 # areg = oreg 0

LDBM 1 # breg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (16383)

STAI 2 # mem[breg (16383) + oreg (2) = 0x004001] = areg (0)

LDAC 0 # areg = oreg 0

OPR 3 # exit 0

Load-store operations

There are two variants of load and store instructions: using absolute addresses

and addresses relative to a base address. Absolute addressing (LDAM,

LDBM and STAM) is intended to access objects in memory that are

allocated at offsets that are fixed with respect to a program, such as constant

values and global variables. Relative-addressing (LDAI, LDBI and

STAI) is typically used to access objects that are relative to a dynamic

position, such as the stack pointer, or index into an array. The particular

variants of load/store instructions is influenced by their targeting from a

compiler. Having pairs of load instructions that can write to areg or

breg (such as LDAM and LDBM) gives flexibility when generating

operands for binary operations, whereas having only single variants of stores (STAM and STAI) fits most cases where expression results generated into

areg need to be written to memory.

Branching

For branching, a relative branch is provided with BR, which can be used, for

example, to reach a label location. Conditional branch versions BRZ and

BRN are used to implement logical binary operations (less than, equal etc) and BRB is an absolute branch that is used, for example, to return to

a calling function using an address retrieved from memory (see example in next section).

Address generation

A special constant-loading instruction LDAP is used to generate bytewise

program addresses, relative to the program counter, such as for branch targets.

The following instruction sequence performs a call to foo but first loads

the return (link) address using LDAP to use with BR. The callee foo

returns to the caller using BRB.

FUNC foo

LDBM 1

STAI 0 # Save caller address

...

LDBI 0 # Restore caller address

OPR 0 # Return to caller

PROC main

...

LDAP lab2

BR foo

lab2

These instructions have the following execution trace:

main+32 LDAP 2 # areg = pc (60) + oreg (2) 62

main+33 NFIX 13 # oreg = 0xFFFFFF00 | oreg (13) << 4 (0xffffffd0)

main+34 BR 1 # pc = pc + oreg (4294967249) (0x00000f)

foo+0 LDBM 1 # breg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (199994)

foo+1 STAI 0 # mem[breg (199994) + oreg (0) = 0x030d3a] = areg (62)

...

foo+10 LDBI 0 # breg = mem[breg (199994) + oreg (0) = 0x030d3a] (62)

foo+11 OPR 0 # BRB pc = breg (0x00003e)

main+35 ...

The X language

The X language is defined in a separate PDF. X is simple enough that it can be compiled using simple techniques to the Hex architecture, whilst providing enough flexibility to express complex programs such as its own compiler (more on that later). X is an imperative language and has features for procedure calling, composition of statements, looping and conditional statements, expressions including function calls, and representation of memory with variables and arrays. To give an indicative example of X programming, the following program implements Bubblesort to sort an array of four elements:

val length = 4;

var data[length];

proc sort(array a, val n) is

var i;

var j;

var tmp;

{ i := 0;

while i < n do

{ j := 0

; while j < n - i - 1 do

{ if a[j] > a[j+1] then

{ tmp := a[j]

; a[j] := a[j+1]

; a[j+1] := tmp

}

else skip

; j := j + 1

}

; i := i + 1

}

}

proc main() is

{ data[0] := 3

; data[1] := 2

; data[2] := 1

; data[3] := 0

; sort(data, length)

}

Limitations of X to note that simplify its implementation are:

-

Arrays are limited to one dimension.

-

No operator precedence to avoid built-in rules so precedence must be indicated explicitly with bracketing (apart from associative operators).

-

Conditional statements (beginning

if) must always have anelsepart to simplify parsing. -

Variables can only be passed by value into procedures.

-

There is no block scoping so variable and array declarations can only be made at global and procedure scopes. Similarly, nested definitions of procedures are not permitted.

Other noteworthy features of X are:

-

There are two types of procedure: processes (using the

prockeyword) that execute a sequence of steps with possible side effects, and functions (using thefunckeyword ) that have no side effects and return a value. -

Names in a program are introduced as definitions of processes or functions, declarations that represent memory locations, and abbreviations that introduce alternative names for expressions, arrays, processes and functions.

-

The scoping and abbreviation rules are defined so that that actual parameters act as abbreviations of the supplied formals. This allows processes and functions to be compiled by either as closed subroutines or by substitution of the body at the call site, either as a source code transformation or compiler optimisation. For example, given the definition

proc foo(val a, array b) is B, it can be called as a subroutine:foo(x, y)or substituted:val a = x; array b = y; Bproviding the names are unique in the procedure. -

A

valofelement allows processes to be called from expressions to generate values, however it is not implemented inxhexborxcmp.

Hex processor integrated circuit

A hardware implementation of the Hex processor is written in System Verilog,

processor.sv,

in just 150 lines. This implementation is single cycle in that all elements of

instruction execution (ie instruction fetch from memory, decode, instruction

memory access and state writeback) are completed in that time. A separate

memory module,

memory.sv

implements a single-cycle random-access memory with two ports: one for

instruction fetch and the other for data access so that they can occur

simultaneously in the same cycle. Note that because memory access time

increases with the memory capacity, a implementation of Hex accessing a large

memory (ie more than a few thousand bytes) would add pipelining to hide the

latency to memory. Some degree of pipelining is standard in processor

implementations. The hardware design is simulated using Verilator, with C++

testbench driver code in hextb.cpp.

Using OpenROAD, an open-source tool chain

for performing synthesis, optimisation and physical layout of digital circuits,

we can compile Hex into an integrated circuit layout in order that it could be

manufactured into a silicon device. OpenROAD uses the

SkyWater Process Design Kit (PDK),

for creating designs in 130 nm process technology, which was a technology first

commercialised in 2001. The PDK is a collection of analog and digital cell

libraries, design rules and tooling. Since OpenROAD uses

Yosys for synthesis, and it doesn’t support

particular SystemVerilog features, I used

sv2v to convert the implementation to plain

Verilog 2005 (see processor.v).

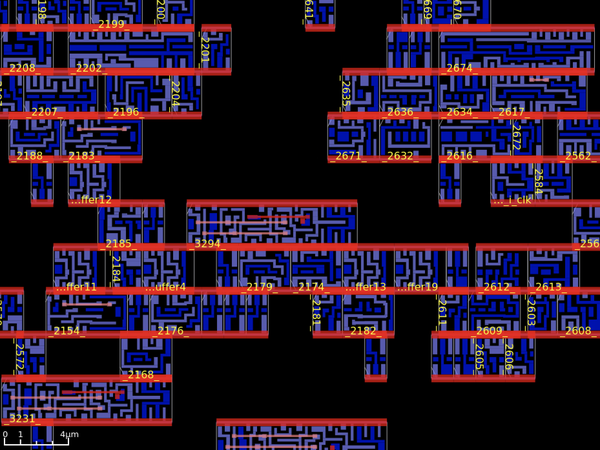

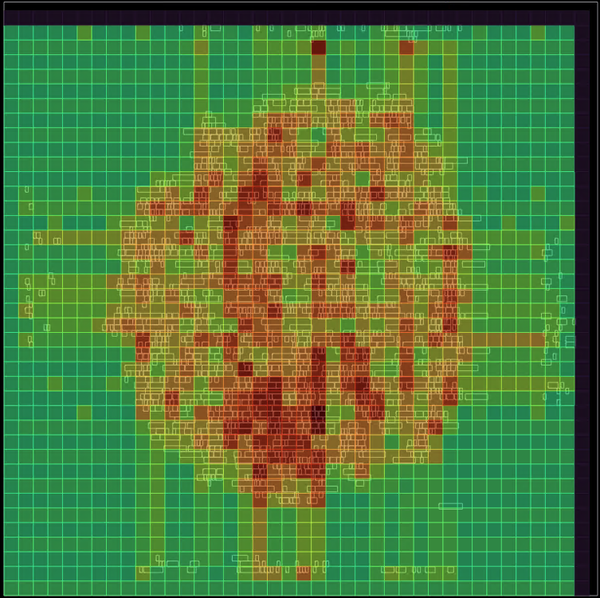

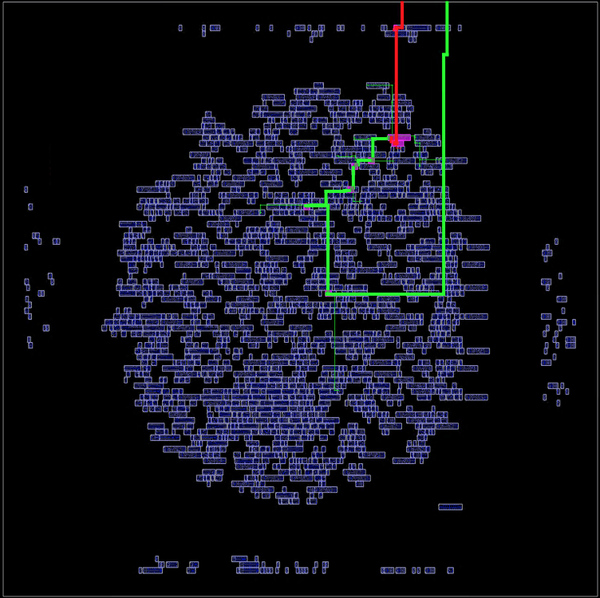

The physical design is based on an OpenROAD default flow, which takes a few minutes to be compiled from the source RTL. The final design has the following characteristics:

- A die size of ~280x280 microns.

- A total of 9,719 standard cells.

- A cell area of 16,706 square microns at 25% utilisation.

- A clock speed of 229 MHz.

- Total switching power of 4.12 mW.

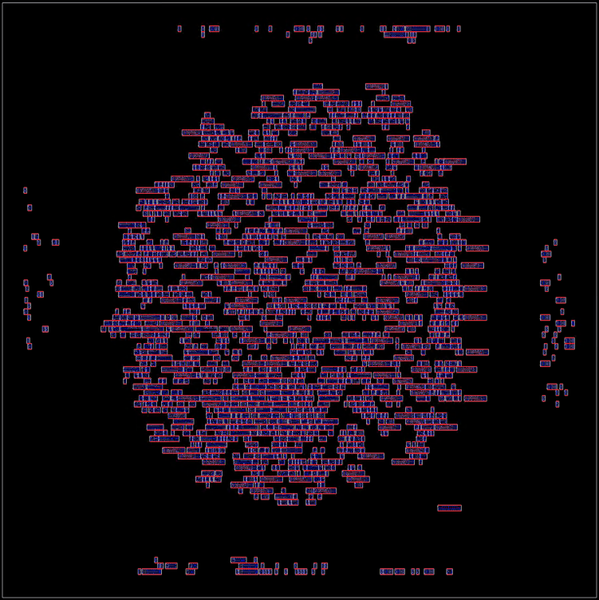

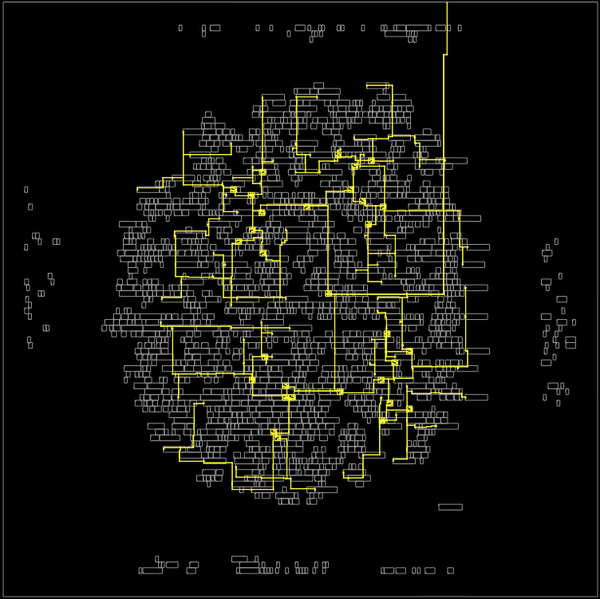

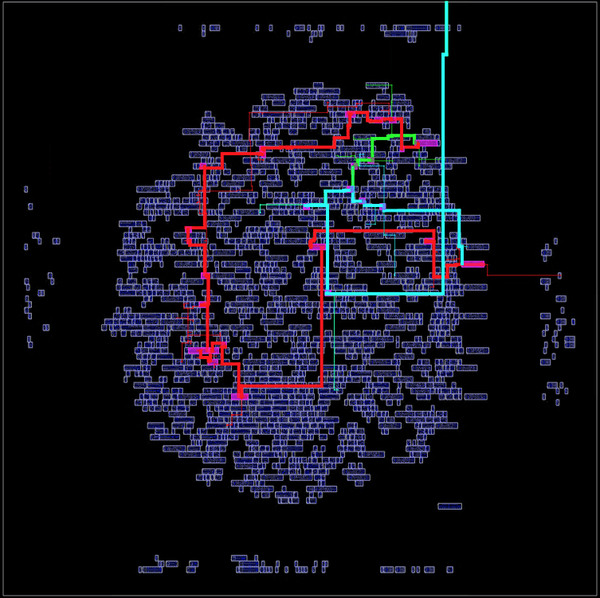

The OpenROAD GUI provides many ways to visualise and explore the design. The following images are some examples of the different views.

Hex tooling

There are three tools provided in the Hex toolchain: a Hex instruction set simulator hexsim, a Hex assembler hexasm and an X compiler xcmp.

Instructions on how to build the tools are included in the

documentation.

The implementation is provided in a small number of source files (with only one

external dependency on boost::format):

-

General Hex definitions are provided in

hex.hppandhex.cpp. -

The Hex simulator is implemented in the headers

hexsim.hppandhexsimio.hpp. (Note that listings for a complete simulator in C are given in the Hex definition (PDF).) -

The Hex assembler is implemented in the header

hexasm.hpp. -

The X compiler is implemented in the header

xcmp.hpp. -

Driver code for the respective command-line tools

hexsim,hexasmandxcmpis implemented inhexsim.cpp,hexasm.cppandxcmp.cpp.

A simple example

Taking a most basic example of an assembly program that simply exits:

➜ cat tests/asm/exit0.S

BR start

DATA 16383 # sp

start

LDAC 0 # areg <- 0

LDBM 1 # breg <- sp

STAI 2 # sp[2] <- areg

LDAC 0

OPR SVC

The assembler can display the program layout in memory and computed symbol values:

➜ hexasm tests/asm/exit0.S --instrs

00000000 BR start (7) (1 bytes)

0x000004 DATA 16383 (4 bytes)

0x000008 start (0 bytes)

0x000008 LDAC 0 (1 bytes)

0x000009 LDBM 1 (1 bytes)

0x00000a STAI 2 (1 bytes)

0x00000b LDAC 0 (1 bytes)

0x00000c OPR SVC (1 bytes)

00000000 PADDING 3 (3 bytes)

13 bytes

And create a 13-byte executable binary:

➜ hexasm tests/asm/exit0.S

This binary can then be simulated with tracing to show what’s going on (the

first column is the cycle count and the second is the pc value):

➜ hexsim a.out -t

0 0 BR 7 pc = pc + oreg (7) (0x000008)

1 8 LDAC 0 areg = oreg 0

2 9 LDBM 1 breg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (16383)

3 10 STAI 2 mem[breg (16383) + oreg (2) = 0x004001] = areg (0)

4 11 LDAC 0 areg = oreg 0

5 12 OPR 3 exit 0

The X compiler can be used to produce more complex Hex programs. Starting with a similar most basic program written in X:

proc main() is skip

This null program is compiled into Hex assembly, where the entry code calls

main then exits, and main does nothing (apart from saving and restoring

the link location):

➜ xcmp tests/x/exit.x --insts-lowered

BR start

DATA 199999

start

LDAP _exit

BR main

_exit

LDBM 1

LDAC 0

STAI 2

OPR SVC

PROC main

LDBM 1

STAI 0

lab0

LDBM 1

LDBI 0

OPR BRB

And when simulated produces the following trace where execution through

main can be seen since it is the only labelled portion of the code:

➜ hexsim a.out -t

0 0 BR 7 pc = pc + oreg (7) (0x000008)

1 8 LDAP 1 areg = pc (9) + oreg (1) 10

2 9 BR 4 pc = pc + oreg (4) (0x00000e)

3 14 main+0 LDBM 1 breg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (199999)

4 15 main+1 STAI 0 mem[breg (199999) + oreg (0) = 0x030d3f] = areg (10)

5 16 main+2 LDBM 1 breg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (199999)

6 17 main+3 LDBI 0 breg = mem[breg (199999) + oreg (0) = 0x030d3f] (10)

7 18 main+4 OPR 0 BRB pc = breg (0x00000a)

8 10 LDBM 1 breg = mem[oreg (0x000001)] (199999)

9 11 LDAC 0 areg = oreg 0

10 12 STAI 2 mem[breg (199999) + oreg (2) = 0x030d41] = areg (0)

11 13 OPR 3 exit 0

The program can also be run on the Verilog Hex implementation using hextb

(which doesn’t provide as rich instruction tracing as hexsim):

➜ hextb a.out -t

Wrote 20 bytes to memory

[11] 8 0x51 LDAP

[13] 9 0x94 BR

[15] 14 0x11 LDBM

[17] 15 0x80 STAI

[19] 16 0x11 LDBM

[21] 17 0x70 LDBI

[23] 18 0xd0 OPR

[25] 10 0x11 LDBM

[27] 11 0x30 LDAC

[29] 12 0x82 STAI

[31] 13 0xd3 OPR

exit 0

Hello World

A more fulsome example is ‘Hello World’, where the main process is simply:

proc main() is prints("hello world\n")

And prints unpacks the bytewise string representation by using routines for

performing division and remainder by 265. The full program listing is:

➜ cat tests/x/hello_prints.x

val put = 1;

val bytesperword = 4;

var div_x;

proc main() is prints("hello world\n")

proc putval(val c) is put(c, 0)

func lsu(val x, val y) is

if (x < 0) = (y < 0)

then

return x < y

else

return y < 0

func div_step(val b, val y) is

var r;

{ if (y < 0) or (~lsu(y, div_x))

then

r := 0

else

r := div_step(b + b, y + y);

if ~lsu(div_x, y)

then

{ div_x := div_x - y;

r := r + b

}

else

skip;

return r

}

func div(val n, val m) is

{ div_x := n;

if lsu(n, m)

then

return 0

else

return div_step(1, m)

}

func rem(val n, val m) is

var x;

{ x := div(n, m);

return div_x

}

proc prints(array s) is

var n;

var p;

var w;

var l;

var b;

{ n := 1;

p := 0;

w := s[p];

l := rem(w, 256);

w := div(w, 256);

b := 1;

while (n <= l) do

{ putval(rem(w, 256));

w := div(w, 256);

n := n + 1;

b := b + 1;

if (b = bytesperword)

then

{ b := 0;

p := p + 1;

w := s[p]

}

else skip

}

}

Compiling and running this shows that it takes ~50K cycles to execute and inspecting the trace is clear to see that most time is spent in the arithmetic routines.

➜ xcmp tests/x/hello_prints.x

➜ hexsim a.out

hello world

➜ hexsim a.out -t

...

48902 61 OPR 3 exit 0

Building an X compiler and bootstrapping

A third example is a complete compiler for X, written in X:

xhexb.x

written by David May in ~3,000 lines of X. This serves as a challenging program

to compile, and interesting that it can bootstrap itself. Using the notation

X(Y) to mean compile source Y using binary X, we can first create an xhexb

binary by running xcmp(xhexb.x):

➜ xcmp -S tests/x/xhexb.x

...

20739 bytes

We can then use xcmp(xhexb.x) to compile Hello World as

xcmp(xhexb.x)(hello_prints.x):

# Create an xhexb compiler binary.

➜ xcmp tests/x/xhexb.x

# Compile Hello World.

➜ hexsim a.out < tests/x/hello_prints.x

tree size: 602

program size: 414

size: 414

# Run it.

➜ hexsim simout2

hello world

Similarly, we can use xcmp(xhexb.x) to bootstrap itself by running

xcmp(xhexb.x)(xhexb.x):

# Create an xhexb compiler binary.

➜ xcmp tests/x/xhexb.x

# Use xhexb binary to compile xhexb.x.

➜ hexsim a.out < tests/x/xhexb.x

tree size: 18631

program size: 17093

size: 177097

# Use the bootstrapped xhexb binary to compile Hello World.

➜ hexsim simout2 < tests/x/hello_prints.x

tree size: 602

program size: 414

size: 414

# Run it.

➜ hexsim simout2

hello world

Implementation details

Both the assembler and compiler are based on the xhexb.x bootstrapping

compiler for X discussed above.

The assembler works in two main phases:

- Parsing the program to form a list of directives (instructions, labels, data etc).

- Code generation to iterate through the directives and emit binary output.

Before emission, the value of labels must be determined, which involves solving two

problems. The first is that for a given relative reference, the length of the

encoding (ie number of prefixes) depends on the value of the reference and vice

versa. This is solved by iteratively increasing the encoding length until it

meets the required range (see instrLen()). The second problem is that the

value of a relative reference depends on the length of any relative encodings

contained within the range. This is solved by iteratively updating label values

until they reach a stable state (see resolveLabels()). The assembler adds

additional rudimentary debug information to the binary, with a mapping of

instruction ranges to symbol values. This allows the simulator to display the

current symbol and offset.

The compiler works a traditional way, structured as a sequence of phases, first creating a parse tree, then performing passes on the tree to optimise it and then lowering the tree to machine instructions:

- Parse the program to form an abstract syntax tree.

- Walk the tree to populate a symbol table with names occurring in the program.

- Walk the tree to propagate constant values within expressions.

- Walk the tree to transform expressions into a canonical form.

- Walk the tree to generate a sequence of intermediate machine instructions.

- Lower the intermediate instructions to machine instructions.

- Optimise the machine instruction sequence.

- Assemble and emit the machine instruction sequence.

Command line options such as --tree are available to inspect the internal

representation of the program in between these stages.

Compared with a more sophisticated compiler, Hex and X afford two significant simplifications. First, the small set of features in X make it straightforward to map to directly to machine instructions rather than an intermediate machine-independent representation. Secondly, the register architecture of Hex means that allocation of registers can be handled easily during mapping to machine instructions, rather than having to allocate physical registers to a virtual set as is typical in machines with more registers.

More details of the xhexb compiler implementation are included in the X

and Hex notes PDF, with aspects such as the

calling convention, handling of operators and arithmetic and memory layout

being shared in xcmp.

A historical note

Hex, apart from being related to the Transputer, has some other interesting historical roots. David May learned about languages and compilers from Martin Richards who was a young lecturer when David completed his final-year Computer Science course as a student at King’s College Cambridge (the first student to do so). Martin was the designer of the influential language BCPL and its portable compiler technology. BCPL found its way to Bell Labs where UNIX was being developed. BCPL was the direct precursor to C and so led to the portability of UNIX.

When David moved from Cambridge to Warwick, the only useful language on the Modular One minicomputer that was available was BCPL but the compiler was incomplete. So David completed the compiler and ported BCPL to other computers, including some microprocessors. Using techniques similar to BCPL’s bootstrapping compiler and interpreter, David designed and implemented a concurrent language (EPL), bringing him into contact with Tony Hoare and Iann Barron (founder of the company that designed the Modular One and also of Inmos).

David employed the same techniques again at Inmos to build the first implementation of Occam in the 1980s and then again in 2008 for the project that led to the founding of XMOS (incidentally, I used this compiler in my PhD work to demonstrate techniques of compiling message-passing programs). Hex and X follow directly from the BCPL-derived approaches, used by David as a tool to teach students about instruction sets, compilers, bootstrapping etc.

Summary

Modern processors, languages, compilers, and tooling are complex and difficult to understand. This note walks through possibly the simplest processor architecture that allows a compact implementation of rudimentary tooling and a complete high-level programming language to be targeted at it. The definitions and implementations are contained in a single repository and just a small set of source files, making it an excellent project to use to explore processors and compilers.

Similar projects

The Big Hex Machine is a giant hands-on implementation of a Hex processor. It was designed and built by students and staff at the University of Bristol’s Computer Science Department.

Here are some other related projects that include simple implementations of processors and/or their toolchains.

-

VSPL, is a very simple programming language designed by Martin Richards to be used as a case study for comparing compiler implementations. The provided source distribution includes several implementations of VSPL in different languages.

-

Experiments in Computer System Design is a walk through of an implementation of a Tiny Register Machine (TRM) in Verilog with serial communication, DRAM access and multiprocessing (Niklaus Wirth, 2010).

-

Selfie is an educational platform for teaching programming languages and runtime systems. It is based on a simplified RISC-V architecture and includes a self-contained self-hosting compiler for a subset of C, an emulator, a hypervisor and a small standard library for the language. These tools are implemented in a single file (~12K lines of code).

-

Luz CPU, a simulator, assembler and linker for the Luz processor architecture written by Eli Bendersky.

-

Nibbler 4 Bit CPU is a complete description of a processor that has been implemented in discreet logic chips.

-

Discrete logic IC CPU us an architecture, discrete-logic implementation and basic tooling including a programming language.

Further reading

-

Processor Design: An Introduction a ground-up explanation of how processors work.

-

LLVM Kaleidoscope Tutorial which walks through an implementation of a simple programming language using LLVM as a backend for code generation and just-in-time compilation.